Set theory is the branch of mathematics that, unsurprisingly, deals with sets. It’s an area of great importance in a number of fields, including computer science.

In this post, I’ll go over a brief review of basic set theory as it pertains to those pursuing an interest in computer science. Let’s just jump right in!

What is a Set?

The first and most logical question we can answer about set theory is just what is a set? Well, a set is simply an unordered collection of objects that contains no duplicates.

So, just what is an object then? Well, an object can be anything really, including sets themselves (in other words, sets can contain other sets). For example, we could be talking about the set of all words in the English language or a set of all positive integers that are multiples of 12. An object can be pretty much anything!

There are two key takeaways here:

- Sets are unordered collections. So, the set {1, 2, 6} is exactly the same as the set {6, 2, 1} which is exactly the same as the set {1, 6, 2}.

- Sets do not allow duplicate items. Some implementations will ignore this limitation, but we’d refer to that as a multi-set, rather than a true set.

Set Notation

We’ve already seen that a set is donated by the use of curly-braces, such as {A, G, J, D} or {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 0}, but what if our set is too large for us to be able to list all of the items. Well, if there is a pattern to the data, we can use ellipses (…) to fill in voids. For example:

- {1, 3, 5, 7, 0, …, 99} -> Represents the odd integers from 1-99

- {5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, …} -> All positive multiples of 5

What about sets where the pattern isn’t obvious enough to use this ellipse notation? Well, for these cases, we utilize set-building notation. Let’s look at an example:

S1 = {x | x is a positive integer > 5 and a multiple of 15}

This would be read as “S1 is a set of elements, x, such that x is a positive integer greater than 5 and a multiple of 15”.

Hopefully this is all seeming straightforward so far!

Set Equivalaence

Two sets, S and T, are equivalent if and only if they contain exactly the same elements (remember, the order of these elements does not matter). A more mathematically formal way to state this would be:

$$S \equiv T \iff \forall x (x \in S \iff x \in T)$$

Just as a quick bit of review, you read the above as “Set S is equivalent to set T if and only if, for all x, x is an element of S if and only if x is also an element of T”. In other words, two sets are equal if any element of one must also be an element of the other.

Subsets

A set S is said to be a subset of set T if every element in S is also an element in set T. This does not imply that the two sets are equivalent. T could contain some elements that S does not. This is more formally expressed as:

$$S \subseteq T \iff \forall x(x \in S \rightarrow x \in T)$$

It should be clear by this definition that any set S is also a subset of itself. That is to say:

$$S \subseteq S$$

This should logically make sense to you since every element in S is clearly an element in S…

Proper Subset

If you think of the subset as being less-than equal to, then we can loosely think of a proper subset as being less-than.

Put more concretely, saying that S is a proper subset of T indicates that S is a subset of T but there exists at least one element in T that is not in S. In other words, all the elements in S are contained in T, but T contains at least one additional element that is not in S. We would indicate this as follows:

$$S \subset T$$

Let’s look at a couple of examples:

$$\{2, 4, 5, 8\} \subset \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10\}$$

$$\{x \mid x \, is \, a \, positive \, integer\} \subset \{y \mid y \, is \, an \, integer\}$$

Special Sets

There are a few special sets that are worth mentioning here.

The Empty Set

The empty set is, as the name would suggest, a set with no objects in it. There is only one empty set (which should intuitively make sense). We represent this set as either:

$$\emptyset \, or \, \{\}$$

The empty set is considered to be a subset of all other sets, including itself. To understand why consider the definition of a subset:

$$S \subseteq T \iff \forall x (x \in S \rightarrow x \in T)$$

Well, there is no element x in the empty set and we know that from a false implication, we can prove anything:

$$FALSE \rightarrow Anything, therefor , FALSE \rightarrow TRUE$$

The Universal Set

The universal set, often represented by U, contains the universe itself, but it’s often defined in a more limited scope so that it’s more useful to work with. For most purposes in computer science, you can simply think of the universal set as being the collection of objects from which we can select specific elements of a given set.

Let’s look at an example:

$$S = \{ x | x \, is \, an \, integer \, and \, x \% 7 = 0 \}$$

In this example, the universal set might be the set of all integers and from this, we might build a particular set S consisting of all multiples of 7.

This concept can occasionally play a pivotal rule in proofs.

Other Named Sets

In addition to the previous two named sets, there are a number of others. A few that often come up are:

- The set of all integers, represented by

$$\mathbb{Z}$$

- The set of all real numbers, represented by

$$\mathbb{R}$$

- The set of all natural numbers, represented by

$$\mathbb{N}$$

Set Cardinality

Set cardinality is often thought of as the size of the set. This is largely true, however, this way of thinking can quickly breakdown when we start looking at infinite sets. We would represent the cardinality of the set S by:

$$\mid S \mid$$

A simple example of cardinality of a finite set would be:

$$if \, S = \{a, b, c\} \, then \, \mid S \mid = 3$$

It’s also mentioning that:

$$\mid \emptyset \mid = 0$$

Countably Infinite Sets

What happens when we start looking at infinite sets? Well, we must first understand that there’s a countable infinity and an uncountable infinity.

A set is said to be countable if, given some value in the set, we can provide the “next” value with 100% certainty.

For example, let’s say that you have the set of all integers and I give you the value 41. From this, you can say, with certainty, that the next integer value is 42. As such, the set of all integers is what we call countable infinity.

We can represent countable infinity as:

$$\aleph_0 \,\, or \,\, \infty$$

Let’s consider some examples for a moment:

$$S_4 = \{4, 8, 12, 16, …\} \,\, I_+ = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, …\}$$

The cardinality of both of these sets are countably infinite:

$$\mid S_4 \mid = \aleph_0 \,\, \mid I_+ \mid = \aleph_0$$

But hang on a minute, that means that the following statement must be true:

$$\mid \mathbb{Z} \mid = \mid S_4 \mid = \mid I_+ \mid$$

That’s right, the set of all integers, the set of all integers that are multiples of 4, and the set of all positive integers all have the same cardinality. This is something that can cause a great deal of unease for some. I mean, S4 is clearly a proper subset of the set of all integers, so how can it possibly have the same cardinality?!

This is simply part of the mystery that comes with dealing with infinities!

This could potentially lead you to assume that all infinite sets have the same cardinality, but this is not the case (more on this later).

Proving Two Sets Have the Same Cardinality

In order to prove that two sets, S and T, have the same cardinality we need to find a “one-to-one” (1-1) function and an “onto” function that maps elements in S to elements in T. If we can find a 1-1 and an onto function, f(), for set S and T, then we can say with certainty that:

$$\mid S \mid = \mid T \mid$$

It’s also important to stress that the above statement is very different than saying:

$$S \equiv T$$

A Bit About Functions

We’ve established that a function, f(), maps elements from one set, S, to another set, T. We can represent this as:

$$f:S \rightarrow T$$

We refer to the set S as the Domain and the set T as the Range. If an element, a, is from the domain S and the function f maps it to an element, b, in the range T then we write it as:

$$f(a) = b$$

Let’s look at an extremely simple example of a function:

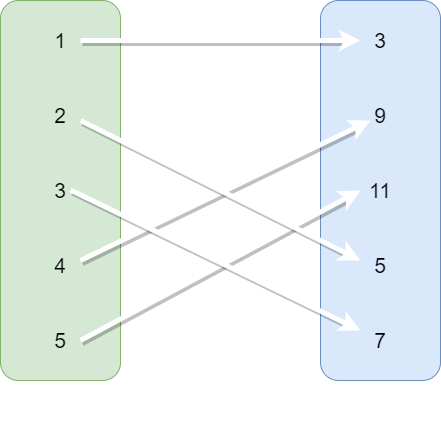

Consider the following sets:

$$DOMAIN \,\, S = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$$ $$RANGE \,\, T = \{3, 9, 11, 5, 7\}$$

The mapping function would be:

$$f(x) = 2 x + 1$$

Additionally, the mappings are as follows:

$$f(1) = 3$$ $$f(2) = 5$$ $$f(3) = 7$$ $$f(4) = 9$$ $$f(5) = 11$$

We can represent this graphically as follows:

Additionally, there are a few other properties of functions that we must keep in mind:

- A function must map every element of the domain set to some element in the range set.

- In general, not all the values in the range, T, need to have values mapped to them. Some may have many values mapped to them while others have none.

- For the purposes of proving cardinality, however, we will see that we will require that all elements of the range T have one and only one value that maps to them.

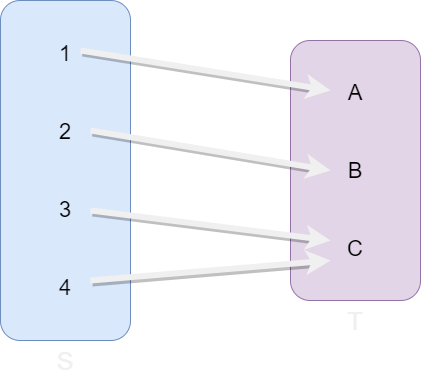

1-1 Functions (Injective)

A function, f(), is a 1-1 (one-to-one) function if, for any two elements, a and b, of the domain, S, then f(a) != f(b). In simpler terms, different elements of the domain S will map to different elements in the range T.

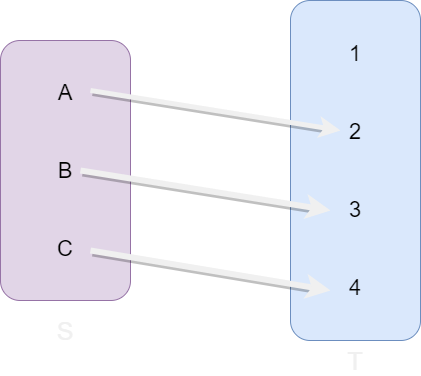

Onto Functions (Surjective)

A function, f(), is an onto function if every element of the range, T, has at least one element of the domain, S, which maps to it. In other words, all elements of the range must have an element that maps to them.

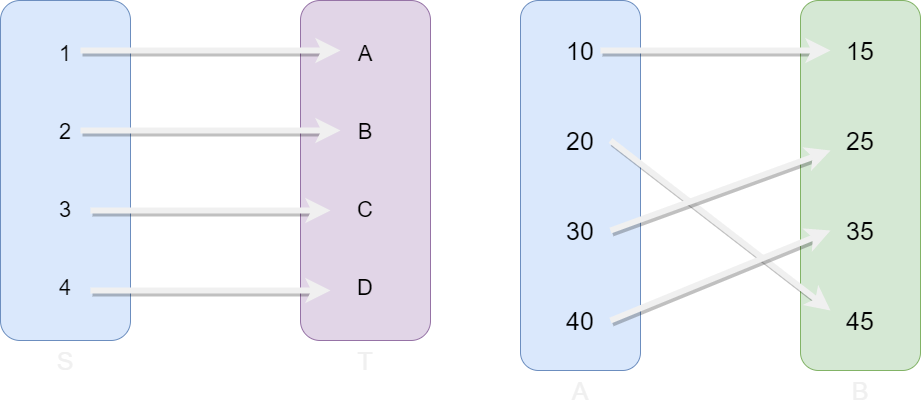

1-1 AND Onto Function (Bijective)

As one may conjecture at this point, a function is 1-1 and onto if it meets the requirements for both a 1-1 function and an onto function.

Proving Equal Cardinality of Infinite Sets

Recall that early we said that the following sets have equal cardinality:

$$S_4 = \{4, 8, 12, 16, …\}$$ $$I_+ = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …\}$$

But, how do we prove:

$$\mid I_+\mid = \mid S_4 \mid$$

Well, as we’ve already stated, we need to find a function, f(), that is a 1-1 and an onto function (that is to say, we need to find a bijective function) to map the set I+ to the set S4. It should hopefully be pretty clear that the following function meets our needs:

$$f(x) = 4x$$

Using this, all elements of I+ are clearly mapped to a value in S4 and all elements of S4 are mapped to by one and only one element from I+. We have therefore found a bijective mapping function and proven that these two countably infinite sets have equal cardinality.

What About Uncountable Infinities?

Okay, so countable infinities should now make sense, even if they do have some strange properties, but what about uncountable infinities? What even is an uncountable infinity? Well, it’s simply a set in which we can’t determine the “next” element with absolute certainty.

Consider the set of all real numbers. Is this set countable?

If you answered “yes”, then you’re wrong! Let’s say that I gave you the element 3.45.

Could you then tell me the next element? You may be tempted to say that it’s 3.46, but this is not the case! Between 3.45 and 3.46 is 3.456 or 3.45679839843754 or any other number of possibilities. In fact, there is an infinite number of values that lie between any two real numbers. Therefore, the set of real numbers is said to be uncountable infinite.

Going beyond this is outside the scope of this review, but this idea of an uncountable infinity is often referred to as the power of continuum, denoted by:

$$ \mathbb{C}$$

As a fun math tidbit, it turns out that the following is true:

$$\mid \aleph_0 \mid \, \lt \, \mid \mathbb{C} \mid$$

Common Set Operations

We will end our brief review of set theory by taking a look at some of the common set operations.

Set Union

The set created by S union T consists of any element that is in either S or T (or both). This is represented by:

$$S \cup T \{x \mid x \in S \mid \mid x \in T \}$$

For example:

$$S = \{a, c, g, 5\} \,\, and \,\, T = \{1, 5, c, 8, h\}$$ $$S \cup T = \{a, c, g, 1, 5, 8, h\}$$

There are a few important properties for unions:

$$(a) \,\, S \cup S = S$$ $$(b) \,\, S \cup \emptyset = S$$ $$(c) \,\, S \cup U = U$$

Set Intersection

We can say that x is an element in the intersection of S and T is x is an element in both sets:

$$S \cap T = \{x \mid x \in S \,\,\&\&\,\, x \in T \}$$

For example:

$$S = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} \,\, and \,\, T = \{2, 4, 6, 8, 10\}$$ $$S \cap T = \{2, 4, 6\}$$

There are a few important properties of intersections:

$$(a) \,\, S \cap S = S$$ $$(b) \,\, S \cap \emptyset = \emptyset$$ $$(c) \,\, S \cap U = S$$

Set Difference

The difference of the two sets, S and T, is a set containing the elements found in S but not found in T:

$$S - T = \{x \mid x \in S \,\,\&\&\,\, x \notin T\}$$

For example:

$$S = \{a, b, c, d, e, f\} \,\, and \,\, T = \{a, c, d, e\}$$ $$S - T = \{b, f\}$$

It’s also important to emphasize that:

$$S-T \neq T-S$$

The properties of set difference are:

$$(a) \,\, S-S = \emptyset$$ $$(b) \,\, S - \emptyset = S$$

Set Complement

The complement of a set, S, consists of the elements of the Universal set that are not in S itself:

$$\neg S = U - S$$

In other words, the complement of a set, S, is the set of elements that are not in S, but that are in the universal set. So, if our universal set was the set of all integers, and S was the set of all odd integers, then the complement of S would be the set of all even integers.

Cross Product (Cartesian Product)

The cross product, also called the cartesian product, of two sets, S and T, is the set of all ordered pairs (x, y) where:

$$x \in S \,\, and \,\, y \in T$$

It’s also important to note that we are talking about ordered sets, so:

$$(x, y) \neq (y, x)$$

Consider this example:

$$S = \{a, b, c\} \,\, and \,\, T = \{1, 2\}$$ $$SxT = \{(a, 1), (a, 2), (b, 1), (b, 2), (c, 1), (c, 2)\}$$

There are a couple of important properties to note about the cross product:

$$(a) \,\, \mid SxT \mid = \mid S \mid * \mid T \mid$$

So:

$$If \,\, \mid S \mid = 4 \,\, and \,\, \mid T \mid = 6 \,\, then \,\, \mid SxT \mid = 24$$ $$(b) \,\, SxT \neq TxS$$

The Power Set

The power set of S is simply the set of all subsets of S. We represent this as:

$$2^S$$

Here’s an example:

$$If \,\, S = \{0, 3, 6\}$$ $$Then \,\, 2^S = \{\emptyset, \{0\}, \{3\}, \{6\}, \{0, 3\}, \{0, 6\}, \{3, 6\}, \{0, 3, 6\}\}$$

It’s important to remember that both S itself and the empty set are all subsets of S.

Additionally, I should mention that the cardinality of a power set is as follows:

$$If \,\, \mid S \mid = x, \,\, then \,\, \mid 2^S \mid = 2^x$$

Just as one last interesting math fact, the following is true:

$$ \mid 2^{\aleph_0} \mid = \mid \mathbb{C}$$

That’s All Folks!

Well, that’s really all I have to get into for today. Hopefully, you found this little review of set theory helpful and everything makes sense to you!